Hawai‘i Then and Now: Portraits of O‘ahu’s Past

DISAPPEARING DIAMOND HEAD, A HISTORIC FIRE IN CHINATOWN AND MULE-DRAWN TROLLEYS. WE LOOK BACK ... AND FORWARD AT HONOLULU.

BY ROBBIE DINGEMAN | PHOTOS BY AARON K. YOSHINO

THE MOANA IN 1920.

ARCHIVAL PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE HAWAI‘I STATE ARCHIVES

Time tinkers with our perspective. That’s partly why looking at vintage photos of familiar places fascinates us, hinting of what has been and what may lie ahead. We visited the Hawai‘i State Archives, the Hawai‘i State Library and the Bishop Museum Archives. We pored through our own images from the past, including a cache of old photos kindly donated by a former Honolulu resident. (More about her later.) We sought uncommon photos that gave us enough specific clues that we could return to shoot the same place in 2018.

We sat down with art director Louis Scheer and photographer Aaron K. Yoshino to plan the best way and best places to capture today’s scenes. While it’s tempting to romanticize the vintage vantage point, some pictures proved interesting for what’s missing: Many of the early Downtown photos show few trees, only some sidewalks and often muddy streets. Travel through time with us.

KING STREET

King Street in the heart of Downtown in 1910 bears some resemblance to the busy thoroughfare of today: rows of buildings, people rushing to appointments. But the bustle of the business district then included horses, as well as trolleys, now replaced by a mix of gas-powered, electric and hybrid cars, trucks, SUVs as well as commercial vehicles of many shapes and sizes.

Clearly, the biggest change is the number of people living and working on O‘ahu. Census records tell us the population of Honolulu County was 82,028 in 1910, 179,359 in 1940 and at last count, that more than quintupled to 988,650 in 2017.

DID YOU KNOW?

HONOLULU THEN AND NOW IS THE TITLE OF AT LEAST THREE BOOKS, INCLUDING PROLIFIC PHOTOGRAPHER RAY JEROME BAKER’S FASCINATING 1941 VOLUME. BAKER SUBTITLED THE COLLECTION “A PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF PROGRESS IN THE CITY OF HONOLULU.” HE ALTERNATED BETWEEN THOSE HE SHOT IN THE 1940S AND OTHERS HE COLLECTED FROM DECADES EARLIER.

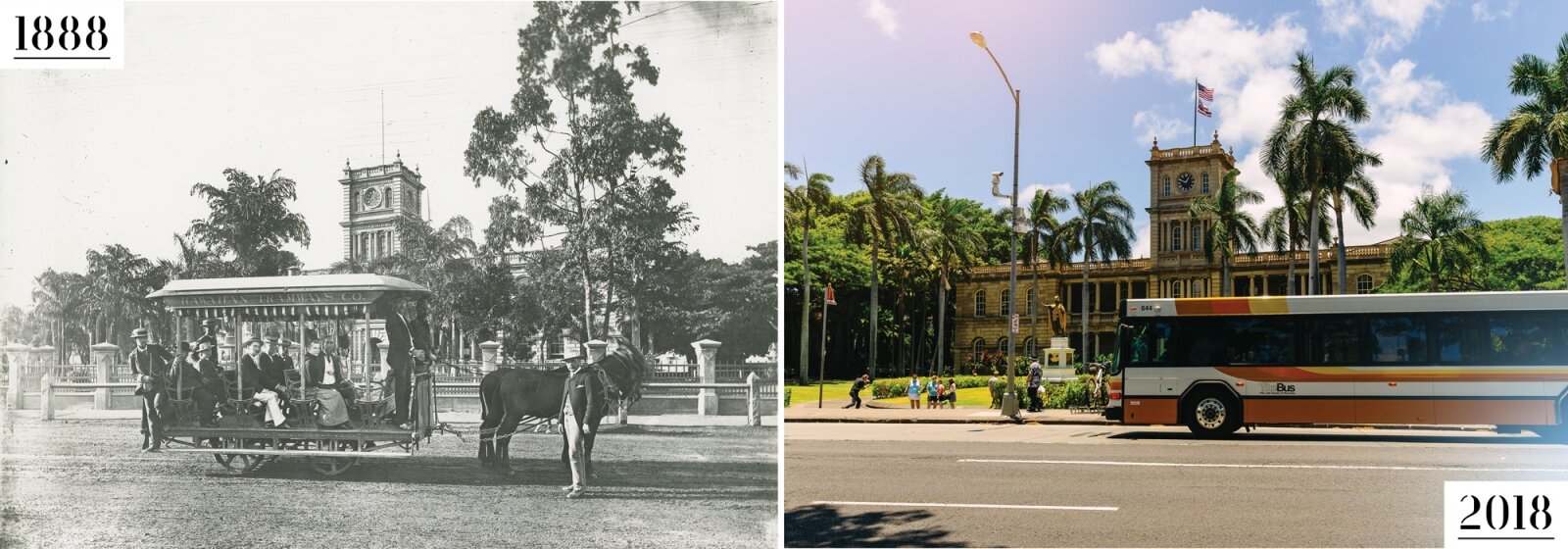

ALI‘IOLANI HALE ON KING STREET

Public transportation already ran along King Street fronting Ali‘iolani Hale. From 1888 to 1903, the Hawaiian Tramway Co. used mule-drawn or horse-drawn vehicles where modern cars, tourist trolleys, city buses and bikes now travel. In 1903, the mule-drawn operation was taken over by Honolulu Rapid Transit & Land Co. Today, government officials continue to debate the plans, the route and everything about Honolulu’s rail project.

The authority building it? HART, which now stands for Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transit. In the 1970s when former Mayor Frank Fasi was trying to build a multimillion-dollar rail project, the acronym stood for Honolulu Area Rapid Transit.

The current cost estimate of the 20-mile project exceeds $8.1 billion. The first phase of the system from Kapolei to Aloha Stadium is now slated to open in late 2020 with the rest of the entire system, from Kapolei to Ala Moana Center, forecast to be completed in 2025.

DID YOU KNOW?

PHOTOGRAPHER BAKER LIVED IN HAWAI‘I FROM 1910 UNTIL HIS DEATH IN 1972 AT THE AGE OF 96. THOUGH HE TRAVELED TO OTHER PLACES, BAKER SOLD IMAGES—PRINTS, POSTCARDS AND BOOKS—DIRECTLY FROM HIS OFFICE AT 1911 KALĀKAUA AVE. BISHOP MUSEUM EXPERTS RECOGNIZED HIS HANDWRITING PENCILED ON THE BACK OF SOME OF OUR PHOTOS.

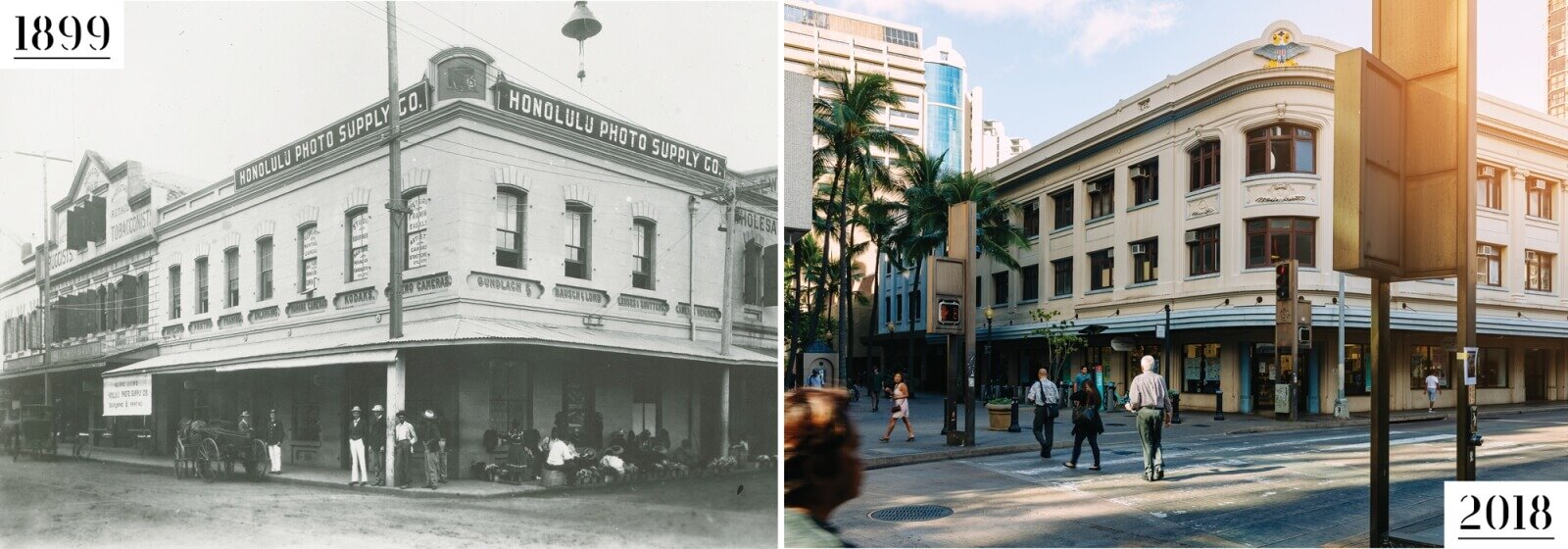

CORNER OF FORT & HOTEL STREETS

This 1899 photo showed a busy Downtown corner dominated by the Honolulu Photo Supply Co. building, which offered developing of a dozen 4-by-5 prints for 70 cents, flanked by a druggist and a grocer. The mix of businesses in the area hasn’t changed that much at this particular corner. Instead of a photo supply, Fisher Hawai‘i specializes in office needs, furniture and school supplies with Longs Drugs, Walgreen’s and Walmart all operating nearby.

Baker expressed disappointment with the city’s growth: “The easygoing, leisurely way of life, when everybody knew almost everybody else, when business was an unhurried procedure and salesmen’s visits took on the nature of prolonged social calls, has gone forever, and in its place have come cafeterias and help-yourself groceries, elaborate displays, pressure selling and a general speeding up of the business tempo. Many strangers have come, and the old-timer who walks the downtown streets of Honolulu may do so without meeting a single person he knows.”

In our modern Downtown, most of us express more day-to-day concern about homelessness than civility.

DID YOU KNOW?

THE FIRST KAUMAKAPILI CHURCH, BUILT WITH TWIN TOWERS IN DOWNTOWN, WAS DESTROYED IN THE FIRE AND REBUILT A MILE AWAY, ON KING STREET. AFTER THE 1900 PLAGUE FIRE WAS EXTINGUISHED, HEALTH AUTHORITIES SET MORE THAN 30 MORE “CONTROLLED FIRES” AND FOUR MONTHS LATER DECLARED HONOLULU FREE OF PLAGUE.

INTERSECTION OF KING & BETHEL STREETS

Some of the historic photos list only a fuzzy time frame or none at all, leaving us to scan the photos closely for clues from vehicles or recognizable buildings. But this newsy photo, looking in the ‘Ewa direction from Bethel Street, refers very specifically to the afternoon of Jan. 20, 1900, when a huge fire loomed over King Street.

At the order of the Board of Health, a fire was set at about 9 that morning to destroy “plague-infested tenements” on Beretania Street near Nu‘uanu Avenue. Another 40 so-called cleansing fires had been set earlier as health authorities also cleaned buildings, burned garbage and filled old cesspools. A rising wind blew the fire out of control, consuming many buildings by the river and waterfront, all in an attempt to stop the spread of bubonic plague. The newspapers of the day reported that the blaze burned for 17 days and wiped out about 4,000 homes over 38 acres, most belonging to Chinese and Japanese communities.

Current King Street shows a modern street. While high-rises have replaced some of the older structures, two of the buildings, complete with awnings at the center of the photos, look not much different than they did 118 years ago.

DID YOU KNOW?

THE LIFE EXPECTANCY IN HAWAI‘I IN 1910 WAS JUST OVER 44 FOR A MALE AND JUST UNDER FOR A FEMALE. IN THE UNITED STATES AT THE SAME TIME, THOSE AGES WERE OVER 48 AND 51 RESPECTIVELY, ACCORDING TO THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, NATIONAL CENTER FOR HEALTH STATISTICS.

MCCULLY AREA

In 1910, kalo (taro) fields—and a near unobstructed view of Diamond Head—dominated the landscape in the McCully area. But the need for housing to support the growing population pushed agriculture out of the now urban community.

Researchers at UH estimate that, at its peak, kalo covered more than 20,000 acres, or 31 square miles, spread over six islands. Today, state agricultural officials estimate there are only about 400 acres in kalo production, even with a continuing cultural and agricultural focus on the staple crop of Native Hawaiians.

Today, the silhouette of Diamond Head can still be discerned from park space along the Ala Wai Canal. Now, field lights stand where palm trees waved and high-rises along Kapahulu and Waikīkī hide the most famous face of Diamond Head from the inland perspective.

The condos to the left include the 36-story Marco Polo, where a fire in July 2017 left four people dead, 13 injured and some 30 units destroyed and caused more than $100 million in property damage that forced many residents out of their McCully-Mō‘ili‘ili homes. Built in 1971 before sprinkler systems were required, the seven-alarm fire prompted a new round of debate about where sprinkler systems should be required.

PHOTO CREDITS:

WHILE WE RECEIVED COPIES OF PHOTOS FROM THE RAY JEROME BAKER COLLECTION FROM DIFFERENT SOURCES, THE PRIMARY RESOURCE FOR BAKER’S EXTENSIVE IMAGES IS THE BISHOP MUSEUM ARCHIVES, WHICH HAS THE LARGEST COLLECTION OF HIS WORK. FOR MORE INFORMATION, GO TO BISHOPMUSEUM.ORG.

KA‘IULANI AVENUE

Consider Ka‘iulani Avenue. A 1910 photo shows the street near the driveway leading to the Cleghorn estate. A typed caption taped to the back of the photo notes that the lovely grounds once “were distinguished by their lofty coconut trees, lily ponds and rich tropical foliage.” By 1940, a tree-lined street of single-story homes still looked somewhat idyllic to our modern eyes even though the area was already being split into lots for cottages. But Baker opined “this former show place of Honolulu could no longer be a source of pride.” Cut to 2018 and Waikīkī has changed from a neighborhood of farms and homes to a forest of hotels and high-rises.

Ka‘iulani Avenue has been slated for more big changes. The 133 Ka‘iulani project calls for leveling the King’s Village complex to make way for a 32-story condo-hotel with 248 units. In agreeing to the redevelopment, the city Department of Planning and Permitting required developer BlackSand Capital turn Ka‘iulani Avenue into a two-way street and pay for up to $1 million in community benefits that could include public parking stalls, art and cultural programs, and outdoor activities. The project has been delayed, in part by a lawsuit filed in September 2017 by a company connected to a previous landowner.

SEE ALSO: Hawai‘i Then and Now: This is What Honolulu Used to Look Like

THE MOANA ON KALĀKAUA AVENUE

In 1896, a wealthy Waikīkī homeowner named Walter Chamberlain Peacock proposed to build a grand beach resort. His Moana Hotel Co. Ltd. commissioned architect Oliver G. Traphagen. The company also hired the Lucas Brothers, who also served as primary contractors for ‘Iolani Palace.

Constructed in 1901, the original four-story wooden hotel building was elaborate from the start. The design combines Victorian styling with colonial clapboard. And, although major additions have been made over the decades to the historic beachfront resort, the wooden center still maintains the honor of the oldest hotel in Waikīkī. When it first opened, each room on the three upper floors included a bathroom and a telephone, plush amenities for any hotels of the time.

Hotel history indicates the operation included an electric generator and ice-making plant as well as a billiards parlor, saloon and library. The early logs show the first group of guests consisted of 114 Shriners who paid $1.50 a night each for the posh lodging. It’s evolved into a modern resort that’s changed hands over the years, but maintained a strong link to legacy. The “First Lady of Waikīkī” is listed on the national and state register of historic places.

MAHALO!

WE ESPECIALLY WANT TO THANK PAT BURDETTE OF WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA, FOR SAFEGUARDING A COLLECTION OF HAWAI‘I PHOTOS FOR MORE THAN 50 YEARS AND THEN MAILING THEM TO US. SHE HAD HELD ONTO THE IMAGES FROM THE EARLY 1960S WHEN SHE LIVED IN HONOLULU AND WORKED IN ADVERTISING AGENCIES.

WAIKĪKĪ BEACH

This early picture of Waikīkī Beach was also from the Baker Collection, but it was one of the rare photos that he attributed to another photographer, crediting Frank Davey who operated in Honolulu between 1898 and 1902.

The photo shows the modest swimsuits of the times and the low-rise heights of many of the buildings. The beach scene seems so uncrowded even when compared to the relative early-morning calm of the present-day photo. While the jaw-dropper is the largely unobstructed view of Diamond Head, the early photo surprises with wooden structures built right up to the waterline, steps and piers that have since been zoned out of existence.

With more than a century between the photos, they both capture a bit of the sheer joy of jumping into the ocean in Waikīkī.